Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Read Tony Long

I'm not a reader of Wired magazine, and haven't been since the 1990s, when their breathless hucksterism for technology was the rage. I can never forget their "Long Boom" issue of 1997, when they predicted that the stock market would continue to grow, and that the world was entering "25 years of prosperity, freedom and a better environment." I'll give them credit for leaving that embarrassment on the web, but then and now, Wired specializes in technology carnival barking, and I, for one, will pass on the freak show.

Except that I've just stumbled across a host of jeremiads written by their copy chief, Tony Long. The latest concerns laptops in higher education. Tony's screeds are terrific. Tony is the rare technology aficionado unimpressed by utopian pronouncements and possibilities. And he's a good writer. So you might want to check him out, even if he's hidden in the bowels of Wired.

Saturday, June 24, 2006

Here is an announcement from a Korean hardware manufacturer of a low-cost, $200-300 PC, although it looks to me more like a thin-client play than a PC play. I'm not a big thin-client fan. I've yet to see a thin client system perform that well, and yet to see a broad array of applications (especially educational software apps) perform well in thin client systems. Still, the positioning seems to be towards the education market, in hopes of providing it a low-cost hardware alternative. And, as I've mentioned before in this blog, you'll see a lot more machines at the low-cost end of the market in the next five years.

Thursday, June 22, 2006

It had to happen. Companies are now marketing cell phones/GPS locators to preteens. As a parent, I actually like the idea. Most interestingly, this article mentions Leapfrog adding educational games to some phones. Tetris math, anyone?

The Compensatory Education Space

Plato Learning has just won a contract at St. Louis Community College to supply online developmental mathematics. I'm not a big fan of Plato products, which tend to be big, cranky, creaky, and ineffective. They've built a business through acquisition and the provision of large, complicated system tools. They are so, well, yesterday.

But I love the space they are moving into. Developmental Math is promising. It's a $35MM annual market, with (unfortunately), lots of growth potential. The vast majority of entering freshmen in community colleges will take this course. To provide for the course you need the full math curriculum from arithmetic to trigonometry, which makes it easy for Plato to enter, and hard for a company like Carnegie Learning, which only has an Algebra product. Were I the curriculum supervisor in this space, I'd buy ALEKs before anything else, since ALEKs was created with Developmental Math in mind, and is a terrific product. My ranking is below:

| Name | Effectiveness | Engagement Level | UI Design | Architecture | Administration | Flexibility | Total Score |

| ALEKs | 90 | 80 | 75 | 85 | 70 | 70 | 78 |

More generally, I love this space. Compensatory Education is where the shortcomings in the American Education system are redressed. Compensatory Education is community college, night school, adult education and professional training. It's where high school dropouts go for schooling when they realize they don't have the job skills to compete in the marketplace. It is where unemployed and underemployed people go for a skills upgrade. It is a huge market, growing daily. The

Best about this space: the consumer makes the purchase decision. Unlike every other market in education (including higher ed), there are virtually no gate keeping decision makers in compensatory education. For the most part the student makes the purchase decision, and evaluates the efficacy of the product offering and result. Which means that the education offered in this space has to work, and it has to work for the student who puts up the time, and money, for the service. So compensatory education providers HAVE to offer a good product. They can't dress it up in research and prestige. They have to teach.

Which makes it a lot more real than "real" education.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Here's some more criticism of MIT's $100 laptop program--focused, like my other posts on OLPC (One Laptop Per Child), on trying to roll out a centralized, government-administered, proprietary program like this. Tony Roberts, head of a charity that supplies refurbished PCs to the developing world, suspects that the private sector will supply cheap computers to emerging markets faster and better than OLPC. He's right.

Moody's has downgraded its ratings on Scholastic stock to junk. Guess that's the problem when your margins are built on hits like Harry Potter. In Scholastic's defense, they've built a series of terrific businesses in places where they hold virtual monopolies: book fairs and clubs, Read 180, etc. They're easily my favorite major publisher when it comes to running their businesses, mostly because they are not burdened by basal sales. The problem at publicly traded companies is that Wall Street likes growth businesses, not mature ones. And monopolies don't tend to grow quickly.

Will Dick Robinson expect the education group to make up the difference? Is that even possible? The question for HBS students is: Can Scholastic innovate? If they can't, neither can the major publishers...

Monday, June 19, 2006

From the Times of India, an online debate about homework for students in India. The tone and focus is somewhat different than you'd get in the United States, organized as it is around this question:

'Why do kids have to do homework even during holidays? Holidays are meant to be enjoyed'.

Friday, June 16, 2006

Scholastic has released a report on the reading habits of children and their families. No real surprises here: despite Laura Bush (or maybe inspired by the success of her husband), we are not a nation of readers. Only about 30% of kids ages 9-11 are high frequency readers; naturally, the children of parents who are themselves high frequency readers tend to read more. About half of all teenagers read with low frequency. Parents are the worst: only 21% of the parents surveyed said they were high frequency readers. And yet both children and adults aknowledge the importance of reading for college and job success.

The survey briefly addresses the role of technology in reading--about 40% of the students said they were reading using a computer, and those that read with computers tended to be overall high frequency readers.

The kids say that they would read more if there were good things to read (an odd thing to tell the publisher of Harry Potter), but one suspects there are other variables at play. At PS 329 in Coney Island today I asked first and third graders what they did on computers, and overwhelmingly the answer was "play games." The children in Scholastic's survey listed as their number two issue with reading that they "would rather do other things."

It would be nice if Scholastic would have found out what those other things were.

Two weeks ago, I posted an essay that predicted that MIT's $100 PC would be eclipsed by similarly priced efforts from the for-profit computer makers. Now comes rumors of a low-cost Apple portable with a flash memory drive, specifically designed for the education market. Since it is only a rumor, I suppose I will have to wait to say:

I told you so.

Thursday, June 15, 2006

Discovering the Fun in Learning.

Effectiveness | Engagement Level | UI Design | Architecture | Administration | Flexibility | Total Score |

95 | 95 | 90 | 95 | 55 | 60 | 82 |

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

I've said it before, and I'll say it again: technology in the classroom is an ineviability. Teachers, parents and administrators may hate it, but the fact of the matter is that technology is sweeping through the lives of children in such a way that they are insisting on using it to advance their educations. The Millenials have grown up with it, and incorporate it into their daily lives. My five year old has her own computer. She's hardly obsessed by it. She does many of the things a five year old did forty years ago: play with dolls, dress up, and ride bikes. But she also plays Headsprout, and Math Games, and this morning, when her American Girl doll's glasses broke, she suggested we go online to find out how to repair them. The Internet is the first resouce for information she thinks of.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

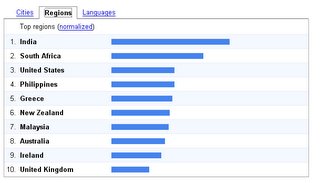

Tutor Vista, an online tutoring service located in India, just secured an A funding round. Look for more educational software and service companies to come out of India. It's a trend, reinforced by some strong economics.

software."

software."In the next five years a major Indian educational software company will join Pearson, Reed-Elsevier and McGraw-Hill as one of the world's major educational publishers. You heard it here first.

Here's a report on yet another committee formed to study technology in the school, this time in Marblehead, Massachusetts. The kicker is at the end of the article, where the interviewee says, "someone involved with curriculum [should] have a background in technology." Well, yeah. But they are hard to find.

Sunday, June 04, 2006

OLPC and the Bottom Line

There's a lot of talk and attention directed lately at MIT's "One Laptop Per Child" (OLPC) program. It's a development effort headed by Nicholas Negroponte, designed to make low-cost, durable computers available for education, especially in the developing world. They've shipped their first prototype, and are understandably excited. They are trying to take on a lot of problems: durable hardware and power supplies that can tolerate sand, heat and variable electric current; fully functional, low-cost software; instructional designs that leverage what we know of student learning in effectively addressing the learning difficulties of impoverished children. They've got a wiki that covers a lot of this, in fascinating detail.

It is an exciting project. The idea that low-cost computers might be available for use by almost everyone on the planet could be revolutionary. It is promising in the way that a lot of the theories of Univeristy of Michigan economist CK Prahalad's theories are promising. If successful, you'd be elevating a generation of poor people whose predecessors had been written off by their nations. And just imagine what all that underutilized talent might do for society.

I could be wrong about this, but I don't think it will go down because of Negroponte and MIT. A lot of this is a little, well, insular. It's an academic project, and has all the breathless intensity of academic projects: great on paper, but less so in practice. The truth of the matter is that businesses are already hunting this underserved demographic assiduously. There is an article in the latest Businessweek that discusses how companies like Intel are busy building low-cost laptops for use by students. And I'm really excited by Microsoft's latest "Pay-As-You-Go" software and financing plan that they've been deploying in developing countries.

Computer hardware and software manufacturers are not going to let a non-profit research project compromise their bottom line. Any truly full-function, cheap PC would do exactly that. Before you know it, the machines would go from emerging markets to developed markets. Everyone would buy a $100 PC if it were as good as the $1600 Dell I’m typing on right now. Those companies know this, and will deploy their own cheap computers (and compensatory for-fee services--think cell phone manufacturers) before long. It's dogma in the computer industry that if your margins are going to be hit, you take the hit and keep the market share. So believe me, Dell, Microsoft and the rest are already hunting that low-end market. And if they aren't, some aggressive entrepreneur is. And will get there before Negroponte.

The economics of this are already at play in the US educational market: hardware and software manufacturers could in theory offer their products at an educational discount and put a laptop in the hands of every American student. They don’t because they want the families of those children (or state governments) to buy them at retail prices.

Those prices are going down, and will continue to do so. In the next two years, the largest single hardware part expense of a laptop (the LCD screen) will finally become cost effective. At that point $100 laptops will be manufactured by Dell, and eMachines, and Lenovo, and any other manufacturer interested in trading price point for volume sales. And $100 laptops will be within the grasp of everyone.

They’ll be fully functional: capable of email, IM, multimedia presentation, etc. And that’s the big difference between them and project like OLPC. The OLPC and other academic initiatives figure that poor people will be happy with dial-up connectivity and limited PC functionality.

But they won’t. Even people who don’t have computers know that they’re capable of magical things. They want in on the magic. All of it.

I’ve spent the last 14 months in some of the worst schools in the United States teaching children from the poorest families in the nation on fully functional Dell laptops. They loved it. They learned from it. And most importantly, they wanted it.

Almost all the children I served asked for the laptops at the end of the program. We couldn’t afford to give them the machines. But I wished I could have, and someday someone will.

My guess is that wish is more likely to be fulfilled by Microsoft than MIT.

Friday, June 02, 2006

The Transference Problem.

Here's a great article by George Mason law professor Thomas Hazlett that encapsulates the objections that opponents have to teaching with computers. His is not the raving of a Luddite. Many people have good, reasoned objections to machine-based learning. Hazlett cites studies where students working on computers actually performed more poorly on standardized tests than students who worked traditionally. He's afraid that technology-enabled learning does little more than teach computer skills. He's on to something.

At Carnegie Learning, we called this the "transference" problem. We saw a lot of it in schools: students would perform well on our software, but then fail offline tests. The learnings they had made on the software didn’t “transfer” to a novel situation. This is a meta-cognitive problem for education generally. It’s difficult to teach in the controlled environment of the classroom such that the students have problem-solving capacity with novel situations in the world outside the classroom. For computer-based education, this is a particularly acute problem because the interactive environment of the computer interface is by necessity limited and controlled. If the interface is built the wrong way, the student can only solve problems with the computer scaffolding built in—they cannot solve problems offline, in novel situations. You might think of the transference problem as the difference between a student researching a paper online and then writing it on his word processor, and a student who simply assembles a paper by clicking and pasting material he has gathered online. One child learns; the other doesn’t.

It's hard to build an interface and human-computer interaction scheme that actually incorporates the student's cognition into the design. It's much easier to simply build around the student interaction. Most software, for example, simply tells students whether they got something right or wrong. This is practically useless from a teaching standpoint: the student needs to figure out what they did wrong in order to learn the things they need to do right. If your interface design doesn’t provide the space for students to do that, they will not learn.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

One week after it acquired PowerSchool from Apple, Pearson has picked up Chancery Software. Clearly, they are making some strong investments in educational software. Interestingly, the latest two pickups are focused on back-end, administrative support. Could it be that Pearson is positioning itself to become the favored application set of administrators, in hopes that one day, when the textbook dollars shift to curricular software, they will be foremost in mind among those who write checks?

Of course, they could be spending that money figuring out what works with students...

Houghton Mifflin bought Achievement Technologies this week for $18.5M. It 's not clear this is a good deal. AT sells Skills Tutor, which is a good, solid program. The market for its offerings is large--HM probably figures it can generate at least $60MM annually in sales with the product. Skills Tutor is a Flash-enabled set of curriculum spanning K-HS. It is well architected, and although it has some subtle failings in both UI design and Human-Computer interaction. Its remediation mechanisms and administrative tools leave something to be desired. Here's my rating on the product:

Effectiveness | Engagement | UI Design | Architecture | Administration | Flexibility | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

70 | 75 | 73 | 78 | 70 | 70 | 73 |

In general, I like this product--it's in the top third of all products I've reviewed. And it is clear why HM acquired them. Because Skills Tutor has an extensive set of programs spanning K-10, it makes HM competitive on breadth with River Deep, Plato and Pearson. What isn't clear is that HM will be able to sell and maintain the product. Houghton bought one of my favorite math products, Larson Learning, last year. I tried to license it for my programs this year, but it was a disaster. Larson got no technical support from Houghton, and no one in sales knew very much about the product, or how to deploy it. In the end, the technical issues were so great that we didn't use the product, even though from previous experience, I was convinced it was effective. Clearly Larson simply threw their product over the wall to Houghton. Thankfully Houghton refunded our money. But if they treat Skills Tutor the same way, it will become another case instance of a good technology that challenged the organizational competency of a major textbook publisher.

This article highlights several promising initiatives in formative assessment using computers. Especially interesting is the emphasis on prices coming down for applications. Which is exactly what it will take to get widespread technology adoption in school. What else it will take: easy to use, at-a-glance interfaces.

Scholastic is a Buy.

Wall street is bullish on Scholastic. And about time: alone among the major educational publishers, Scholastic has a good strategy for getting technology into the classroom. They are busy developing the alternative sales channels (especially after school) necessary to demo technology and overcome technophobic resistance. They are building good technology products these days (especially Tom Snyder), and selling them the right way.

The other major publishers? Pearson ostensibly is the leader in technology, but nothing I've seen indicates they have a nuanced grasp of it, or know how to manage it the right way. For the life of me I can't see why this analyst is bullish on McGraw-Hill. In my experience they were the slowest of the majors in educational technology, and are devoted to protecting their lucrative bottom-line in textbooks.

iPromise iPod

iPromise iPodApple continues to promote iPod as a platform for education--although you have to wonder how serious they are about this. At SIIA in San Francisco last month, the chief of education for Apple, John Couch, gave quite a sales pitch on iPod as an education platform. He was focused especially on iPod as a place to review Podcast assignments. Much of what he suggested was a straight up pitch for Apple products. At best, he and Apple had devised a curricula around multimedia presentation building, and high school students would benefit by understanding how to create multimedia (which I suspect many of them need no instruction in whatsoever).

Here's how you will know Apple is serious about iPod as an educational platform: when they offer the device for an academic discount to schools, and undercut their sales as a consumer player. But that will never happen.